Early Earth Subduction

Plate tectonics is one of the defining features that makes Earth unique among the rocky planets. It drives mountain building, volcanism, and the long-term cycling of materials between Earth’s surface and deep interior. At the heart of this system lies subduction, where one tectonic plate sinks beneath another. Despite its importance, we still don’t fully understand how or when subduction first began on Earth.

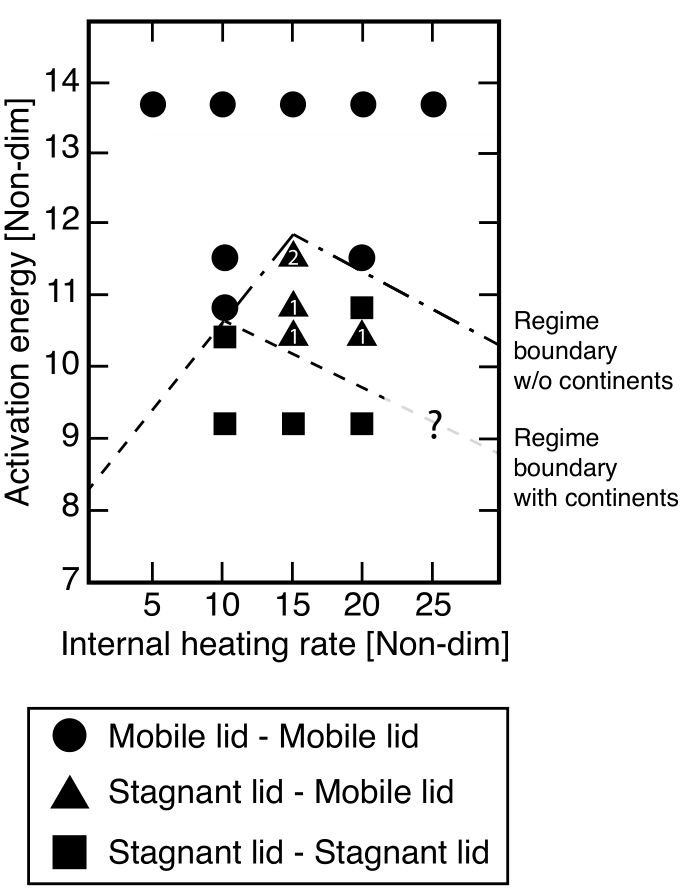

A central focus of my research is understanding how subduction began and evolved during Earth’s early history. I’m particularly curious about the conditions that allowed the first subduction zones to form, and whether primitive continents played a meaningful role in triggering them, or if other factors, like mantle temperature and weakening process, were more influential. I’m also interested in how subduction on the early Earth may have looked different from what we see today. Higher mantle temperatures, more vigorous convection, and differences in the composition and structure of early continents could all have led to subduction zones that were more transient, shallower, or lacked well-defined downwellings compared to those observed on modern Earth.

Fluids, Melts, and the Formation of Early Continents

I am also interested in how fluids and melts produced in subduction zones may have contributed to the formation of Earth’s earliest continents. In particular, I use numerical models of subduction with fluid migration to explore how water released from the downgoing slab could generate buoyant, felsic crust (such as TTG-like compositions) in the overlying plate. By linking slab dynamics, fluid pathways, and melt production in a unified framework, this work aims to better understand how subduction-related processes may have helped build and stabilize the first long-lived continental nuclei on early Earth.

Deep Learning-Based Image Segmentation

In addition to studying the geodynamics of early Earth, I’m also interested in developing computational tools that can help analyze complex geophysical models more efficiently. One area I’ve focused on is using deep learning (specifically image segmentation techniques) to detect subduction zones in numerical simulations of mantle convection. I trained a type of neural network called a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) to recognize subduction zones directly from model output images. FCN learns to identify spatial patterns that represent subduction by analyzing labeled examples. Once trained, it can automatically segment new images to highlight subduction zones, even in models with complex or evolving dynamics. This method goes beyond traditional techniques that rely on fixed thresholds (like temperature or velocity gradients), offering a more flexible and accurate way to track where subduction occurs.

By integrating geodynamic modeling with machine learning, this approach offers a scalable and adaptable way to analyze complex geophysical data. Looking ahead, I envision this tool being used not only to identify subduction zones in numerical models but also to detect a wide range of features (e.g., mantle plumes in mantle convection simulations, mineral phases in microscopy images, impact craters in planetary surface data, etc.). Its ability to learn and recognize patterns directly from images makes it a versatile framework for interpreting diverse geoscientific datasets.